Software preservation: a stepping stone for software citation

This blog post was originally published on Generation R (https://doi.org/10.25815/0ZBH-2W14).

In recent years software has become a legitimate product of research gaining more attention from the scholarly ecosystem than ever before, and researchers feel increasingly the need to cite the software they use or produce. Unfortunately, there is no well established best practice for doing this, and in the citations one sees used quite often ephemeral URLs or other identifiers that offer little or no guarantee that the cited software can be found later on.

But for software to be findable, it must have been preserved in the first place: hence software preservation is actually a prerequisite of software citation.

Preservation: why is it important?

Software preservation is not a simple task. There are many use cases and the complexity of software may lead to different solutions for each of them. One can find various approaches to describe a software system, for example, in [Matthews et al. 2010], an identification schema is proposed with 4 elements:

- Product,

- Version,

- Variant

- and Instance

but up to now the focus has been mainly on archiving software executables only. While an executable software artifact can be reused in certain circumstances (if the hardware and Operating System for which it was built still exists… a ‘big if’ when time goes by) it is often stripped of all the human knowledge a software source code may contain and is readable only by a machine. The executable is definitely important as a tool but it can’t be interpreted, studied or modified. That’s why the preservation of the source code is crucial if we want to keep the technical, functional and cultural knowledge a software may contain, especially when dealing with research software.

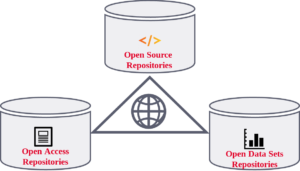

In the scholarly ecosystem, the quest for making scientific results reproducible, and pass the knowledge over to future generations depends on the preservation of the three main pillars: scientific articles, that describe the results, the data sets used or produced, and the software that embodies the logic of the data transformation[Di Cosmo and Zacchiroli 2017].

Software Heritage: preserving the source code

Software Heritage is an initiative aiming to collect, preserve and share all software source code, our software commons. The project was started in 2015 by Inria and has grown over time into a small and dedicated team led by Roberto Di Cosmo and Stefano Zacchiroli. As a non-profit organization Software Heritage will provide an infrastructure capable of responding to multiple stakeholders in a variety of situations.

Behind the scenes, the engineers created a mechanism that is actively crawling repositories (a task that we call listing) and collecting everything new it finds (a task that we call loading). The Software heritage archive is the largest software source code library to date and contains more than 83 millions repositories (as of 6.6.2018)

The current sources of the software are:

- live and updated regularly: GitHub, Debian

- one shot archival: Gitorious, Google Code and GNU

- in progress: Bitbucket

This is a significant head start, but it is still a long way to go to achieve the monumental task of archiving all software source code from development forges, package managers, repositories, FOSS distributions and even single URLs not hosted on major forges (which is the case with many researchers publishing their software on their personal page).

Software deposit: publish the source code and promote Open Science

Researchers in many domains are using software for their work and some are creating software to support their research. For data, there are many organizations, initiatives and working groups promoting the FAIR data principles, yet software is a new actor in the field and making software discoverable and open source is still not the default. Furthermore, finding the correct metadata to cite software is even more difficult. The CodeMeta initiative [CodeMeta 2017] and the CITATION file format[Druskat 2017] are two projects providing a metadata schema to enable citation by including a metadata file inside the source code. Unfortunately, these metadata files are really scarce today.

To promote Open Science and Open Source Software a new collaboration has emerged between Software Heritage, Hal-Inria and the CCSD. It has resulted with a new type of scientific deposit in the French national open archive. Researchers have now the possibility to deposit software source code on Hal-Inria: the open archive of Inria- The French Institute for Research in Computer Science and Automation [Barborini et al. 2018]. With this new possibility, research software is pushed with the submitted metadata to the Software Heritage archive and a swh-id (an intrinsic identifier) is returned by Software Heritage. The citation format on Hal-Inria, inspired by the software citation principles [Arfon et al. 2016], includes the swh-id which is a direct access to the archived software source code.

The swh-id: a digital finger-print for a software artifact

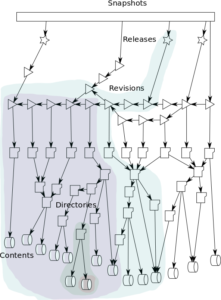

Source code is massively duplicated across projects and across forges, hence, as explained in more detail in [Di Cosmo and Zacchiroli 2017], the data model used for the Software Heritage archive is a Merkle direct acyclic graph (DAG) [Ralph C. Merkle. 1987] . Using this structure, each object present in the Software Heritage archive is associated with an intrinsic identifier computed through cryptographic hashes.

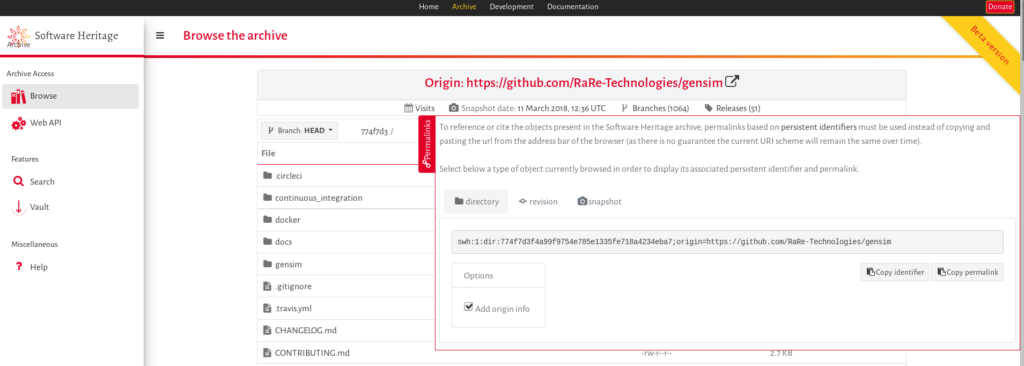

These identifiers are guaranteed to remain stable over time, and are resolved with a persistent identifier schema directly on https://archive.softwareheritage.org/<swh-id>, described in the [persistent identifiers documentation]. To access the persistent identifiers a Permalinks box is available on a side tab and provides identifiers for the current directory, revision (a commit on a particular branch) or snapshot (the complete set of branches in a version control system):

And the great advantage of the swh-ids is that they are now already available for all the billions of software artifacts stored in the Software Heritage archive: yes, that means that you can reference all kind of software, not just the few projects that have proper metadata attached!

The metadata challenge

Many challenges are still ahead. As noted in [Katz. 2017] giving credit to the developers and finding the appropriate metadata for citation can’t be solved by Software Heritage alone. However, Software Heritage fulfils the need of software preservation, that is a stepping stone to proper software citation, and we are planning on extracting the metadata included in the source code in AUTHORS, CONTRIBUTORS, README, LICENCE, codemeta.json, CITATION.cff and other metadata files. That’s why we urge all researchers and developers to include metadata files in their source code and keeping these files updated.

You are welcome to visit our online browse-able archive on https://archive.softwareheritage.org/ where you can search through the more than 80 million origins urls, browse the contents, obtain an swh-id and download a directory or a revision. Enjoy !

References

[Matthews et al. 2010] B. Matthews, A. Shaon, J. Bicarregui, and C. Jones, “A framework for software preservation,” International Journal of Digital Curation, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 91–105, 2010. doi:10.2218/ijdc.v5i1.145

[Di Cosmo and Zacchiroli 2017] Roberto Di Cosmo and Stefano Zacchiroli. 2017. Software Heritage: Why and How to Preserve Software Source Code. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Digital Preservation, iPRES 2017.

[CodeMeta 2017] Matthew B. Jones, Carl Boettiger, Abby Cabunoc Mayes, Arfon Smith, Peter Slaughter, Kyle Niemeyer, Yolanda Gil, Martin Fenner, Krzysztof Nowak, Mark Hahnel, Luke Coy, Alice Allen, Mercè Crosas, Ashley Sands, Neil Chue Hong, Patricia Cruse, Daniel S. Katz, Carole Goble. 2017. CodeMeta: an exchange schema for software metadata. Version 2.0. KNB Data Repository. doi:10.5063/schema/codemeta-2.0

[Druskat 2017] Druskat, Stephan. 2017. Citation File Format (CFF). Zenodo. doi:10.5281/zenodo.1003150.

[Barborini et al. 2018] Yannick Barborini, Roberto Di Cosmo, Antoine R. Dumont, Morane Gruenpeter, Bruno Marmol, et al.. The creation of a new type of scientific deposit: Software. RDA Eleventh Plenary Meeting, Berlin, Germany, Mar 2018, Berlin, Germany. 2018, 〈https://www.rd-alliance.org/rda-11th-plenary-poster-session〉. 〈hal-01738741〉

[Arfon et al. 2016] Smith, Arfon M., Katz, Daniel S., Niemeyer, Kyle E., & FORCE11 Software Citation Working Group. 2016. Software citation principles. PeerJ Computer Science, 2, e86. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj-cs.86.

[Ralph C. Merkle. 1987] Ralph C. Merkle. 1987. A Digital Signature Based on a Conventional Encryption Function. In Advances in Cryptology – CRYPTO ’87, A Conference on the Theory and Applications of Cryptographic Techniques, Santa Barbara, California, USA, August 16-20, 1987, Proceedings (Lecture Notes in Computer Science), Carl Pomerance (Ed.), Vol. 293. Springer, 369–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/3-540-48184-2 32

[persistent identifiers documentation] https://docs.softwareheritage.org/devel/swh-model/persistent-identifiers.html.

[Katz. 2017] Daniel S. Katz. 2017. Software Heritage and repository metadata: a software citation solution. Daniel S. Katz’s blog. https://danielskatzblog.wordpress.com/2017/09/25/software-heritage-and-repository-metadata-a-software-citation-solution/

—Morane Gruenpeter